Vroom Vroom. Do I see you?

In our digital age, we must cultivate our ability to pay attention. Or, as L.M. Sarcasas once suggested, we shouldn’t call it “paying” attention — some things are so valuable they mustn’t be commodified. Should we instead say “give attention,” as in, “what are you giving your attention to?”

This language is helpful but creates a new problem. It assumes that all attention is active; something we have a choice to give, as if it was always under our control. In other words, can we receive attention?

There’s a difference between seeing and looking. To see is to have your eyes open, and to look is to be active, to direct your gaze, to give your visual attention. But what about our passive visual attending, our seeing? We don’t give it. It just, you know, happens. We hardly think about seeing. But what we see has changed drastically thanks to modern technology. I’ll get there in a moment.

Similarly to seeing and looking, we hear (passive) and listen (active). To hear is simply to have a functioning auditory organ. But to listen is to direct one’s ears toward a certain place or thing. Perhaps you’ve been in a crowded room and discovered this ability: if you focus, you can quiet some chatter for the sake of hearing certain others. Or when outside, you pause to take in the sounds of the bird songs or the machine crew working in the distance. They were always there. We always hear them. But we don’t always listen. It seems the ability is “in our heads,” as, through our intentional focus, we “turn down” the volume on some audio inputs and not others. It seems to me that all human persons, in their natural state (without any disease or defect), will hear, but only some will live a listening life.

A great deal of digital attention advice is about the active side: cultivate your listening and looking, tune your eyes and ears to the person across from you or the cardinal in the sky. This is good. We need to talk more about giving attention through listening and looking, through active intention.

But again, what about passive seeing and hearing? Something I wanted to raise in my article for Mere Orthodoxy is the way in which modern life does not merely demand our activity, but numbs and thwarts our passive learning functions as well. Our noisy world has changed what we learn, muting our hearing and blinding our sight. It is in our control as much as living without the need to ever use a car is in our control. It’s difficult.

There are loose ends I need to tie on this point, as I’m not satisfied with where I’ve landed, and, to be honest, I am very tempted to turn this into a long, meandering set of thoughts in search for answers I do not have. For now, I want to get practical and consider cars.

For whatever reason, and I’m sure the engineers had one, modern cars have tinted windows. It isn't easy to see the faces of other drivers and passengers. You can, but it takes effort and can only be done when you’re not actively driving. From time to time, at a stopped light, I will look at the faces of my fellow car commanders. I will try to see them. I thought this might be weird, but a friend recently comforted me when she said she does the same. Amid traffic, long lights, my mind’s ever-growing podcast idea list, intruding thoughts of whether I embarrassed myself yesterday, construction, the radio, the podcast, or the playlist — amidst all that, there are faces in those cars.

For two or three years, I biked to and from work. At the time, I listened to bike infrastructure advocates and resonated with their views. I remember someone disputing the claim that “bicyclists shouldn’t wear headphones” with the counterpoint, “drivers shouldn’t have music on or their windows down.” I was caught off-guard by my own shock. I didn’t realize how normalized it is for car drivers to separate themselves, or at least their ears, from the world around them.

Regardless of urban planning politics, what is at the root of all these design choices? Why is it normal? Why are the tinted windows up and the headphones on in the first place? Perhaps for safety and privacy. Perhaps because that management podcast will give you the tactic you need to get through tomorrow’s meeting. Perhaps the comfort of air conditioning and the entertainment of music. Perhaps there are good reasons. But perhaps these are all distractions. Is not a driver the pinnacle of Pascal’s man in a quiet room alone? So, instead of silence, we’ve built a culture that has removed our opportunities for reflection and, more than that, removed our neighbor from our eye and ear. This really is the normal state: you will never sit down in a taxi cab or an Uber car without the radio on.

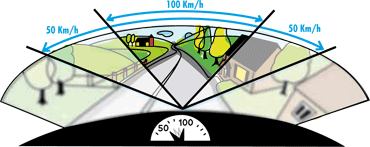

The men who were going down from Jerusalem to Jericho all “saw the man” in Jesus’ parable. The priest “saw the man.” The Levite “saw the man.” And then the Samaritan too, “saw the man.” According to researchers, a driver’s peripheral vision is reduced as the car increases in speed. Rarely would someone walk from Jerusalem to Jericho today: it’s 29km, an eight-hour walk. I wonder if we are not Good Samaritans because we do not see the man.

The bible has much to say about the relationship between knowing and loving. I won’t provide the argument here but will say they are more synonymous than not. It is impossible to be a lover of the one you never knew.

But the thing nagging me in all this is whether some defaults in life cannot be overcome, at least without great effort. I worked at the University of Waterloo and helped design one of their resident buildings. One of our goals was to increase the amount of interactions between students. We put the elevator waiting area directly in sight of the cafeteria. When getting off the elevator, students have an automatic sightline to the student lounge on each floor. If you want to decrease loneliness, increase student satisfaction, and even increase learning (as studies show a connection between student community and academic learning), then you will ensure the students see one another.

I had a small impact on a small building in a big city. Much is outside of our control, and some individual changes seem burdensome. Will I really request that my next car not have tinted windows? Will I turn down the opportunity to learn from a biblical scholar in one headphone as I bike to a friend’s house? Will I turn off my air conditioning and open my windows so I might better hear my neighbors when they arrive home?

I haven’t come up with any radical changes to my life yet. I still own a car, listen to podcasts, and keep the windows closed as I drive. I’ve tried turning off the sound and opening the windows sometimes. Some good. I’m not sure. Perhaps I need to relearn how to walk. Or at least bike more like I used to. It would help me slow down. Though, as I alluded to earlier, modern life makes this difficult.

I’m not going to feel guilty about everything and everyone. Some barriers are okay. I cannot love everyone. Jesus once only invited three of his disciples to a prayer meeting and at other times turned away those who asked for his time. It’s good to have priorities as long as we, in as far as it depends on us, listen.

I want to regain a sense of proximity of those who are already in my life. I want to regularly cleanse myself of the “plasma of connectivity” embedded in my mobile device by keeping it away.

I need to relearn hearing and seeing for the sake of love. I need silence. I need quiet.

I need to sit in a quiet room alone. Maybe then I will better hear the people outside it.

I have recently joined Wyatt Graham and Phil Cotnoir in starting a new podcast called Word and Words. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple, YouTube, or wherever you listen to your podcasts. Our first episode is about pursuing glory.

My plans for the What Would Jesus Tech podcast continue. In fact, I’m half done with what I hope will be a six-chapter mini-book to help people think through their relationship with technology. The goal would be to have it available for small groups to study, discuss, and apply together. I’m not sure whether I’ll publish all the chapters here or share them with other websites. My goal isn’t to make money (it is difficult any writer to do that, Christian or not). My goal is to share the six most important laws of technology so that Christians can use technology like Jesus would if he lived today.

I officially start my PhD in October. Writing here at Whatever Is Noble will continue as time allows, likely monthly—sometimes more, sometimes less. Thanks for reading.

This article came back to mind as I read a thought about the word attention from a book about the Holy Spirit:

“The source of any profound human response is not the responding person, but the presence to which one responds. That is what creates the experience: awareness and recognition towards a beautiful thing, or towards a truth. I don't work it out, think it out. I have a sense, rather, of waiting for it, waiting for a disclosure. It is already there, ungrasped; I must relax, be still, to catch it. Attendre, attention, attendant, en attendant - all these words seem to suggest that tension of listening, waiting to be spoken to, waiting for something that is going to be said. But what brings these acts? What brings me and that truth together? What makes that beauty present to me? What makes me attentive to it?”

Quoted from the introduction to the 2004 edition of The Go Between God by John V Taylor

I haven’t read much beyond this, but I have an inkling that I know what the big picture answer to those quoted questions is, presented in the rest of the book… (it’s the Holy Spirit.)

Sharing in case this provides an interesting lead for future writing.

An interesting read Andrew. I recently was wanting to encourage a friend. My written word to her was 'I see you'. Simply put, I wanted her to know she was noticed.

I relayed that I was listening intently to her circumstances. I couldn't change them, although I assured her of my prayers. There's comfort in being seen and being known that takes conscious looking. You've encouraged me to quiet the worlds noise one step further to continue looking with intent.

Thanks for that.