When Christian AI Books Are Written By AI

Where is the line between a human author and an AI-author?

Let’s consider three Christian books on AI.

The Age of AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity was written by Jason Thacker in 2020.

AI Goes To Church: Pastoral Wisdom For Artificial Intelligence was written by Todd Korpi in 2025.

AI for Theological Education was written by Artificial Intelligence under the supervision of Thomas E. Phillips in December 2024.

That wasn’t a typo. The third book was primarily written by an AI tool (they don’t say which AI model they use). Thomas Phillips is a Professor of New Testament Hermeneutics at Northwind Theological Seminary.

The first book, by Thacker, was published before the launch of ChatGPT. I can trust that when I read Thacker’s book, I’m getting to know a human’s perspective. When I read Phillips’ book, I know upfront that I’m not learning straight from Phillips.

Interestingly, though Thacker’s book is five years old, it speaks at a principle and biblical level and is still relevant today. Phillip’s book tends to be more practical, and it seems it was written with an older AI model (it lacks the deep research of 2025 AI models). Though less than a year old, the book written by AI is already outdated.

Now let’s consider the second book. I placed it in the middle for a reason. A very small portion of the book was written by AI, while most was not. It was published in 2025, which already raises some questions (which all authors must now face) about the extent of AI involvement. And my suspicion grew as I read the following sections of Todd Korpi’s book:

Following OpenAI’s release of their custom GPT feature in 2023, I created a custom GPT, a limited-memory AI version of “myself.” The KorpiGPT bot has learned from my previous writing and other publicly available content and can make recommendations about future projects with ease. While I don’t use the bot for the actual writing process, KorpiGPT has been an invaluable tool to help me create outlines, edit content, and be a brainstorming aid that has saved me from countless hours of staring at “the drawing board.”

On the back end of a lot of my larger writing projects, I use Grammarly’s masterful AI-powered resources to make recommendations in the editing process. I tend to be verbose, so Grammarly helps me trim down my word choice. I also tend to be needlessly snooty in my word choice, and Grammarly helps me temper that tendency in favor of a better blend of readability and sophistication. (page 16)

Here we learn that Korpi doesn’t use AI for “the actual writing process.” But what does he mean by that? He goes on to describe how much time he has saved in brainstorming ideas, saving “countless hours.” To me, the tasks of brainstorming, selecting, and organizing concepts is an essential aspect of the writing process. It’s what makes my writing mine. Spellcheck with AI makes sense. I’ve used Grammarly, too. But brainstorming? Hmm…

In a section on technical AI terms, Korpi passes the job of writing over to AI:

I want to offer some basic definitions for words commonly used in conversation about and around AI… for our purposes, I’ve asked ChatGPT to provide some working definitions. With only a little tweaking, this is what ChatGPT has to say about, well, itself: … (the definitions are then provided across page 19 and 20).

Having asked ChatGPT to do the work, instead of doing it himself, it’s not surprising that many of the definitions are rarely revisited later in the book. Perhaps Korpi’s unstated intention was to demonstrate the helpfulness of AI. In general, Korpi emphasizes what AI can do and underemphasizes what AI is.

Later in the book, Korpi says:

I’m not suggesting that AI write a pastor’s sermons. Instead, it should be an indispensable aid in the sermon planning and creating process. For example, in the fall of 2023, a friend reached out to me for some feedback on his sermon series plan for 2024. There were large themes he wanted to make sure that they touched on, but he had been racking his brain for a few hours to no avail. I created a ChatGPT prompt with the parameters he was looking for and within seconds had a rough draft of a sermon series plan. He liked the plan but wanted to make some tweaks to better align it with the liturgical calendar, so I prompted ChatGPT again, and it revised the plan to those parameters.

With ChatGPT in hand, the two of us went back and forth over the course of half an hour, creating an outline for each of his sermon topics and texts for the entire year . . . a task to which many pastors devote countless hours within any given year… In this situation, AI was a sermon planning aid — helping get the stuck wheels of creativity freely moving again. It was not a crutch to avoid time in prayer and study, and ultimately my friend defers to the leading of the Holy Spirit as he approaches each individual sermon. But it helped bring cohesion and organization to what he already had on his heart for the people God has called him to serve. (page 101)

In Korpi’s own words, AI has become an “invaluable tool” and “it should be an indispensable aid.”

But what is the cost of this?

Even if Korpi carefully limited his use of AI to only the instances he listed, I admit to being skeptical of whether or not I was actually reading his words throughout the book. How much has been ideated through KorpiGPT or rephrased with Grammarly? This isn’t to say that this isn’t a human-written book. I learned a lot about Korpi through the book. He deeply respects his wife. He thinks AI is cool. He likes N.T. Wright. He dislikes Donald Trump. He hates proof-texting verses out of context. He wants his readers to grow in their love of God and neighbour.

I’m not here to write a book review. My friend Austin Gravley has already written an excellent review of Korpi’s AI Goes to Church.

What I’m observing is my growing skepticism about the things I read, and whether I’m interacting with a human being or a stochastic parrot.

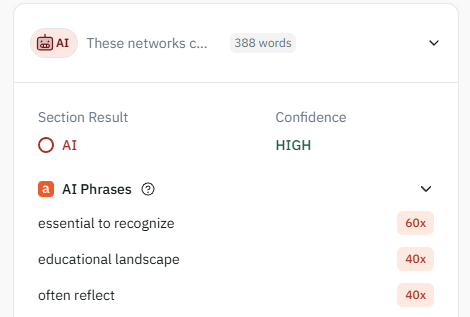

I even copied around 1500 words from Korpi’s book and put them into one of the leading AI Detector programs (Pangram, which isn’t perfect but seems helpful, as it compares text to known phrases used by generative AI). The report came back saying that the sections I quoted from Korpi’s book were human written, and it gave a high-confidence rating. For comparison, the third book (the one that says it was authored by AI), was found to be written by AI. Here are some related screenshots from Pangram:

I think my skepticism is good and bad. Positively, I will be grading assignments next semester and I should have an eye for AI-writing. Professors must adapt to a new era of cheating.

Negatively, my suspicions are dehumanizing to the people I read. By entertaining the idea that their book is written by AI as I read it, I create an unnecessary barrier between their words and my soul.

More should be said. I’d love to discuss solutions. Perhaps we might think of John’s desire to see others “face-to-face” rather than writing a longer letter (2 John 12). Perhaps we might think of Jesus’ incarnation. Perhaps we might think about Paul’s call to love others; love “believes all things” (1 Cor. 13:7). Is my growing skepticism a failure to love my neighbour?

For now, I’m not offering a solution. I’m wrestling with a problem. All technologies include unintentional side effects. I worry about what AI writing does to my love of books.

I wrote a new article for The Gospel Coalition Canada: Would Jesus Use TikTok?

For a time I considered writing a book for What Would Jesus Tech (the podcast I cohost with Austin Gravley and Joel Jacob). I decided against this as I focus my writing in other areas (publishing is hard work). But after a year of sitting on three chapters of the six I had planned, I realized my time is committed to other good things at time point, and so I am prioritizing them. I’m thankful for The Gospel Coalition Canada and am glad to publish with them.

How Should Christians Talk About AI?

New WWJT episode:

Certainly are some challenges in this new world of prevalent, free generative AI tools! I'm also a professor and don't like having the suspicion of AI use hanging over every written assignment. I've been working on a solution called Human Creative (humancreative.org) that seeks to solve this challenge by using an online editor that live tracks the creation of text, provides AI guardrails, and gives readers a way to verify human origin. Let me know if you'd like to try it out!

------

The above is Certified Human Content™. Verify at https://api.humancreative.io/certification/019a9cbb-fe9b-7000-953b-efeb1c0d25e1/

Definitely issues to consider! I've begun using AI more and more-- particularly in rhe kitchen! I'm not interested in becoming a master chef, but ideas for repressing 5 cups of spaghetti squash that my kids didn't enjoy the first time around? I'm happy to let AI do the heavy lifting!